Free-falling with Sense HAT

By Russell Barnes. Posted

Why do astronauts on the ISS float? Find out with our experiments into gravity

Advertisement

Get started with Raspberry Pi – everything you need to know to start your journey!

Ask most people why astronauts like Tim Peake float around on the International Space Station and there is a good chance they’ll say, “Because there is no gravity.” If you think about it, this can’t be the case. The ISS orbits the planet at 400km, but the Moon is nearly 100 times further away and is still subject to Earth’s gravitational pull. So why are astronauts weightless? It’s because the ISS is constantly in free fall, and so the astronauts living inside it experience weightlessness.

The full article can be found in The MagPi 46 and was written by Richard Hayler. If you like this tutorial, you can find more in our Essentials book, Experiment with Sense HAT

This can be difficult to wrap your head around, so we’ll use the Sense HAT to explain it.

You’ll need

Python 3 sense_hat, evdev & select libraries

Something to provide a soft landing

A charged power bank

If you’ve been following the previous Sense HAT Science articles, this should all be familiar now: attach the Sense HAT to your Pi and power it up. Open IDLE3, or just type python3 in a terminal window, and then import the SenseHat library and connect to the board:

from sense_hat import SenseHat sh = SenseHat()

There are a number of ways we can measure motion, forces, and orientation with the Sense HAT: it has a gyroscope, magnetometer, and an accelerometer. We’re going to use the accelerometer, and the line of code we need probably won’t be a surprise:

sh.get_accelerometer_raw()

We’re using _raw() as it returns results in Gs. One G is equal to the force of gravity on the Earth’s surface (9.8m/s), and you often hear jet planes, spacecraft, and even roller-coasters described in terms of how many Gs their riders experience.

The three values measured by the Sense HAT – x, y, and z – correspond to the pitch, roll, and yaw axes. If we run the following Python snippet:

while True: print(sh.get_accelerometer_raw())

…then we should see a continuous stream of the x, y, and z values displayed on screen. Jiggle and wiggle the Pi and Sense HAT around and see how the numbers change. Can you carefully move the Pi so that just one of the axis values changes?

Taking readings

For our experiment, we need to able to record x, y, and z readings constantly and save them to a file so that we can analyse them later. To make things easier (and to make our data file smaller), we will use the joystick to start and stop recording. There are several ways of doing this with Python, but the code uses the evdev library to register joystick presses.

To run the experiment, power the Pi up from a battery pack and secure the two together using rubber bands or cable ties. Start the code and then disconnect the keyboard, mouse, and display cables.

Now find somewhere from where you can drop the Pi. The greater the distance it falls, the easier it is to see the free-fall period. However, don’t forget that you need a big, soft landing zone!

When you’re ready, press the joystick and you should see the 8×8 LED matrix light up all green. That means data is being recorded, so bombs away! Once the Pi has landed, press the joystick again to end the logging (the LEDs should briefly flash red, then turn off completely).

Analysing the data

For the data analysis, we can also use the Pi. Plug all the cables back in and start up LibreOffice Calc. The code conveniently writes the data into a CSV format that can easily be ingested by this (or any other) spreadsheet program, which can be used to plot graphs of our data.

From the graph, you should see that before the drop, the Sense HAT accelerometer measures approximately +/-1G, then falls/rises to 0 while it is falling. You’ll probably also see the ‘bump’ corresponding to the landing (hopefully not too big).

So, now we’ve shown that a falling object will experience zero G, we can see why astronauts on the ISS appear to float. However, if the ISS is constantly falling, why doesn’t it just crash into the Earth? This is because the Space Station is also moving ‘forward’ at a speed fast enough to ensure that it keeps missing the Earth and stays (falling) in orbit.

You can, of course, use the Sense HAT to measure forces greater than 1G, too. Try taking your portable Pi and Sense HAT on a playground ride or, for some serious Gs, a theme park attraction. If you’re going to take your Pi and battery pack on a roller-coaster, though, make sure it is securely stowed away in a zippable pocket!

Code listing

Download gravity.py or type it up from below

from sense_hat import SenseHat

from datetime import datetime

import sys

from time import sleep

from evdev import InputDevice, ecodes, list_devices

from select import select

import logging

# Use the logging library to handle all our data recording

logfile = “gravity-”+str(datetime.now().strftime(“%Y%m%d-%H%M”))+”.csv”

# Set the format for the timestamp to be used in the log filename

logging.basicConfig(filename=logfile, level=logging.DEBUG,

format=’%(asctime)s %(message)s’)

def gentle_close(): # A function to end the program gracefully

sh.clear(255,0,0) # Turn on the LEDs red

sleep(0.5) # Wait half a second

sh.clear(0,0,0) # Turn all the LEDs off

sys.exit() # Quit the program

sh = SenseHat() # Connect to SenseHAT

sh.clear() # Turn all the LEDs off

# Find all the input devices connect to the Pi

devices=[InputDevice(fn) for fn in list_devices()]

for dev in devices:

# Look for the SenseHAT Joystick

if dev.name==”Raspberry Pi Sense HAT Joystick”:

js=dev

# Create a variable to store whether or not we’re logging data

running = False # No data being recorded (yet)

try:

print(‘Press the Joystick button to start recording.’)

print(‘Press it again to stop.’)

while True:

# capture all the relevant events from joystick

r,w,x=select([js.fd],[],[],0.01)

for fd in r:

for event in js.read():

# If the event is a key press...

if event.type==ecodes.EV_KEY and event.value==1:

# If we’re not logging data, start now

if event.code==ecodes.KEY_ENTER and not running:

running = True # Start recording data

sh.clear(0,255,0) # Light up LEDs green

# If we were already logging data, stop now

elif event.code==ecodes.KEY_ENTER and running:

running = False

gentle_close()

# If we’re logging data...

if running:

# Read from acceleromter

acc_x,acc_y,acc_z = [sh.get_accelerometer_raw()[key] for key in [‘x’,’y’,’z’]]

# Format the results and log to file

logging.info(‘{:12.10f}, {:12.10f}, {:12.10f}’.format(acc_x,acc_y,acc_z))

print(acc_x,acc_y,acc_z) # Also write to screen except: # If something goes wrong, quit

gentle_close()

Russell runs Raspberry Pi Press, which includes The MagPi, Hello World, HackSpace magazine, and book projects. He’s a massive sci-fi bore.

Subscribe to Raspberry Pi Official Magazine

Save up to 37% off the cover price and get a FREE Raspberry Pi Pico 2 W with a subscription to Raspberry Pi Official Magazine.

More articles

Get started with Raspberry Pi in Raspberry Pi Official Magazine 161

There’s loads going on in this issue: first of all, how about using a capacitive touch board and Raspberry Pi 5 to turn a quilt into an input device? Nicola King shows you how. If you’re more into sawing and drilling than needlework, Jo Hinchliffe has built an underwater rover out of plastic piping and […]

Read more →

Win one of three DreamHAT+ radars!

That’s right, an actual working radar for your Raspberry Pi. We reviewed it a few months ago and have since been amazed at some of the projects that have used it, like last month’s motion sensor from the movie Aliens. Sound good? Well we have a few to give away, and you can enter below. […]

Read more →

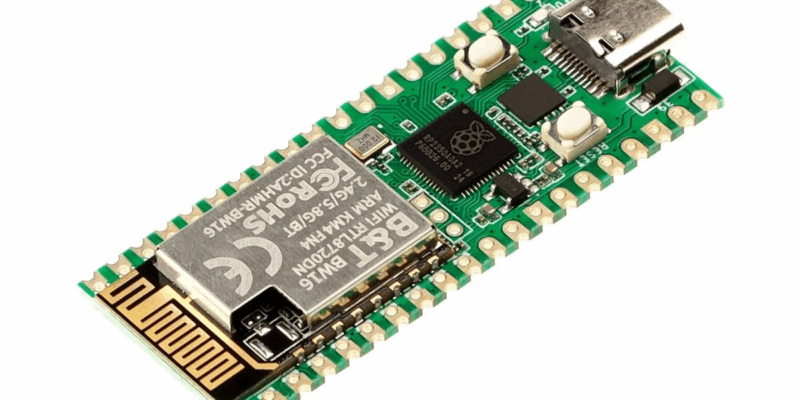

RP2350 Pico W5 review

It’s Raspberry Pi Pico 2, but with a lot more memory

Read more →